Y I rite

I didn't have a subscription to Sports Illustrated magazine when I was a kid. Too expensive. Luckily, my parents' friend Eddie (Sully) Sullivan would bring over a dozen or so of his past issues when he stopped by for coffee occasionally on Saturday mornings.

I would disappear for days to pore over every page of the magazines (and not just the swimsuit issue). Despite its "Illustrated" title, I loved the writing by greats like Frank DeFord, Robert Creamer, William Nack, John Underwood, Tex Maule and others. It made me love words as much as sports, and I have tried -- poorly -- over the years to imitate the styles of these superb writers.

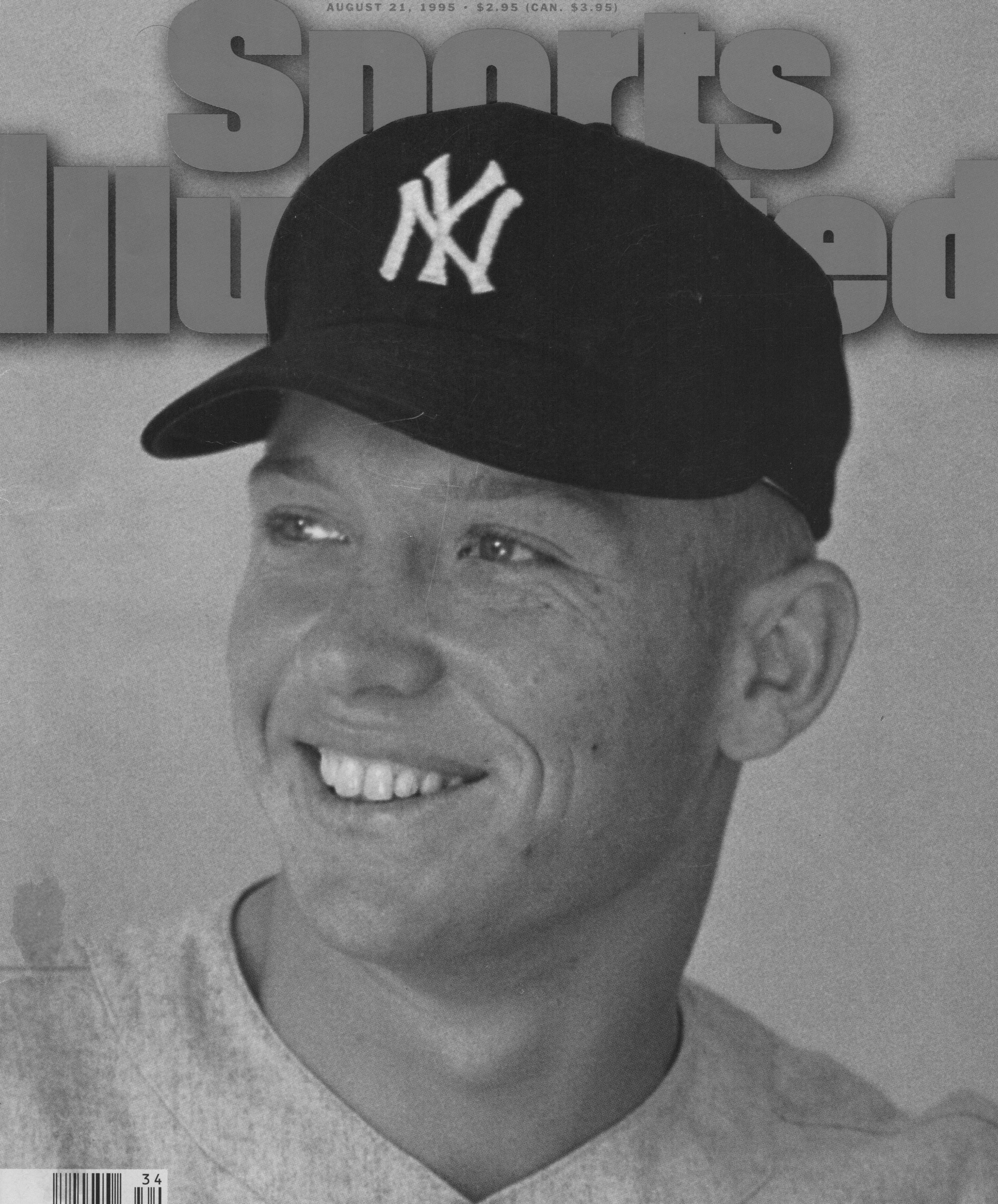

They led me to start my career in sports writing at my college and hometown newspapers. To this day, I think much of the best newspaper writing is in the sports section. Read this amazing opening paragraph from George Vescey of the New York Times on the death of Mickey Mantle:

"People will mourn the tortured man with the hollow eyes and prematurely wrinkled face, whose liver went fast, just as his knees had done. But the real reason they are mourning Mickey Mantle today is that first he was a young lion who prowled green urban pastures, sleekly, powerfully, unpredictably."

SI's cover when Mickey Mantle died in 1995.

I had inspirations beyond sports. My English teacher at Hudson (NY) High School, Frank (never Sully) Sullivan, lit a fire in me for reading. I was an indifferent student in most subjects but not his class. Still, I often got the answer wrong when called upon, to which Mr. Sullivan would respond, "Oh dear boy, it is better to remain quiet and be thought a fool than to open one's mouth and remove all doubt."

He taught me that to be a good writer, you have to read good writing. Although I could have done without the torture of Silas Marner (I constantly fell asleep reading it), he introduced me to great storytelling. I was riveted by Truman Capote's In Cold Blood and Shakespeare's Henry V (the latter of which Mr. Sullivan made us read while standing on a chair, theatrical sword in hand).

Covertly, because it wasn't cool in high school, I drank up everything in his class and supplemented it with my own reading. Roger Angell of the New Yorker and author of numerous baseball books taught me words such as "expunged" (a team wasn't "eliminated" from the playoffs, it was "expunged.").

I also read Edwin Newman's Strictly Speaking and William Safire's On Language columns in the New York Times. Even though I'd rather read Silas Marner again than diagram a sentence, my interest in words and language continues today with books such as Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen by Mary Norris, a long-time copy editor at The New Yorker.

Mr. Sullivan helped me get one of the highest scores in the class on the Regents English exam, much to the surprise of my classmates because I also got some of the lowest scores in other subjects. That test score, and an essay I wrote on journalism, helped me get into Siena College with an otherwise lackluster academic record.

At Siena, an American Literature Between the Wars course introduced me to Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Steinbeck. Reading Hemingway was like a punch in the stomach and made me realize how wordy and pedestrian my writing was. My professors usually agreed. On the cover of a term paper, one wrote, "Gary, I am not sure what point you are trying to make. I guess the only thing I can say is your footnotes are well done. C-"

After college, daily journalism improved the clarity of my writing but then 25 years in politics and business gunked it up with legal grit and corporate residue. An exception was what I learned from GE CEO Jeff Immelt. His writing is authentic, empathetic and energetic. His response to Sen. Bernie Sanders in the Washington Post is the kind of courageous and clear writing that is in short supply in business. Working with him on his annual share owner letter and speeches made me determined to knock the muck off my writing.

So this is why I write. It's fun to think back and recreate things that have happened in my life. Plus, it's a differentiator in the workplace; good writing, after all, is about clear thinking and simplicity, which many big organizations lack. And you need not look past Winston Churchill, Teddy Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan to know that great leaders are often great writers, a combination that is sadly lacking today. In his 1946 essay, Why I Write, George Orwell provided four main motives for authors, and perfectly captured today's politicians:

"Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind."

Powerful. But Orwell knew his writing was imperfect, as do I. I also know that the more I write, the better it will get. I hope communications students, particularly, feel that way.

We need young people to better represent their amazing ideas and deep passions if they are to be fully realized and lived. A PowerPoint slide won't do.

We need leaders -- CEOs, presidents, mayors, educators -- to compel, persuade and explain. A sanitized "holding statement" won't do.

We need bold words like Lincoln's second inaugural, FDR's first inaugural and Martin Luther King's civil rights speech at the Lincoln Memorial. A Tweetstorm won't do.

We need great prose and poetry (go Bob Dylan!) to inspire, entertain and unite us around common values and ideals. Slogans won't do.

Good writing can do these things but most people don't try because it can be risky and is just plain hard. Orwell wrote, "Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a bout with some painful illness." Maybe so. But, with apologies to Mr. Sullivan, I'd rather give it a try and be thought a fool than to not try at all.